Have you been in a situation where nobody at the airport can help you with your lost luggage?

That's an 'accountability sink!' It's when no one has the authority to solve your problem. The power is so spread out that everyone you ask can't really help, so they just keep sending you to someone else.

In a recent blog, Tim Harford explained the functioning of independent monetary policy as an accountability sink. Here is an excerpt:

Consider the idea of an independent monetary policy, when an elected government sets an inflation target and then an unelected central bank has the task of trying to hit that target…

When the Bank of England hurts millions by raising interest rates, it can point to its inflation mandate. When people complain to the government, the government can say that interest rates are a matter for the Bank of England. It’s an accountability sink again, but monetary policy is almost certainly better as a result of the fact that somehow nobody is to blame.

— Tim Harford, Who’s responsible for our accountability problem?

I’ve been thinking about the accountability of central banks for a while now, particularly the Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

One might say that RBI gained true independence in 2016 with the Finance Act, 2016 which led to the adoption of flexible inflation targeting. A Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) was set up, which would primarily adjust the policy repo rate to keep inflation in the band of 4% consumer price inflation, with a tolerance band of +/- 2%. If annual CPI inflation remains in the range 2% - 6%, the MPC has done its job well.

But why bother about MPC’s accountability?

The broad consensus is that the MPC has done a good job. The MPC and flexible inflation targeting regime are decidedly better than previous monetary policies in India1, but I’d be cautious to call it an absolutely redeeming success just yet.

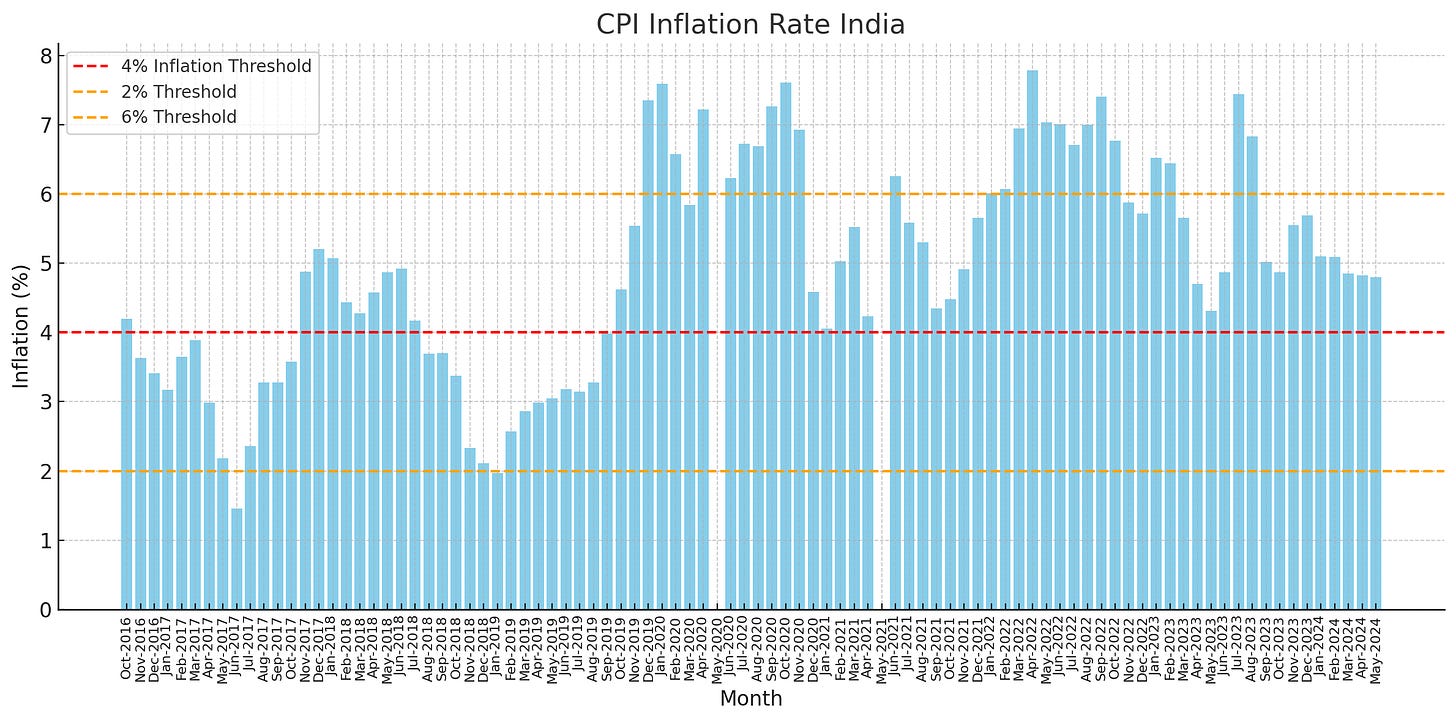

In the period October 2016 to May 2024, annual CPI inflation rate has exceeded 6% in 25 months of the 92 months period. That’s 27% times. All of these periods have been after December 2019. And in 2020 and 2022, inflation remained more than 6% for over 9 months consecutively. Why did the RBI fail in this period, and what did it plan to do differently? We don’t know. I’ll explain later in this piece.

Also, while the inflation target is supposed to be 4% +/- 2%, there’s an asymmetry in the distribution, with the rate of inflation exceeding 4% in 64 of the 92 months.

A Public Choice view of the MPC

The MPC is composed of 6 members — the RBI Governor, two other members from the RBI, and three external members. The MPC meets at least once every 2 months and votes on the policy repo rate. In case of a tie, the RBI Governor’s vote is considered the deciding vote. This structure gives too much power to the Governor.(This is also recognized in Example 5 of Chapter 6 in Vijay Kelkar and Ajay Shah’s book, In Service of the Republic (2019 edition)).

Each member’s vote and the rationale for the vote is made public. The idea is that the members face reputational costs when they make poor decisions, and thus aligns their incentives to make the right decision. This does not only mean that decisions in bad faith are made costly, but even mistakes on good faith are also costly — and there’s an incentive to avoid them, and if made, then to correct them in future decisions.

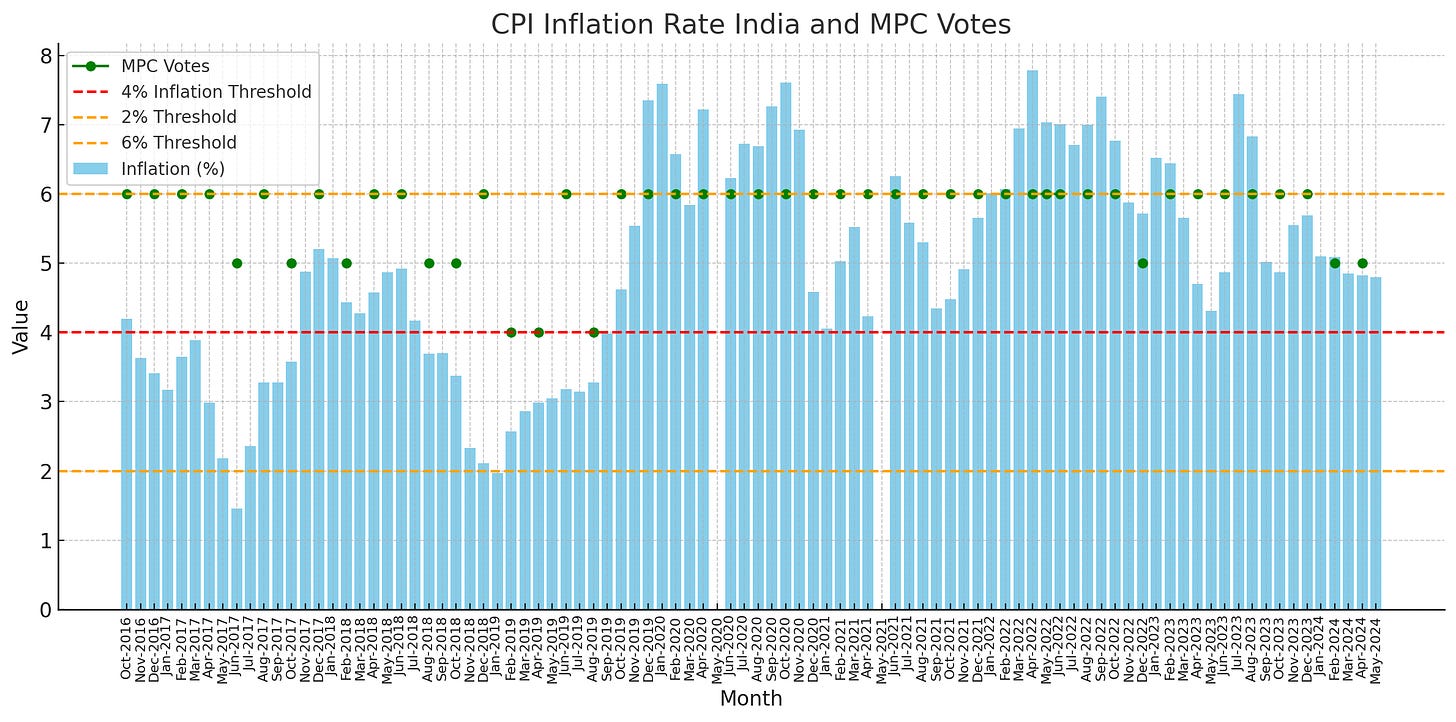

Given the structure, my first hypothesis was that the RBI staffers would have very little incentive to cast a vote against the Governor’s vote. My analysis of the 48 MPC meetings since October 2016 revealed that only 3 of the 96 votes by RBI staffers were against the Governor’s vote. That’s only 3.1% votes! At first glance, my hypothesis seemed confirmed2.

But, I looked at all the votes. Turns out, among the external members, only 12 of the 144 votes (8.3%) were against the Governor’s vote. 36 of the 48 decisions by the MPC were unanimous; 9 decisions were made with a 5 to 1 majority; and 3 decisions were made with a 4 to 2 majority.

What explains this level of unanimity?

One explanation is that the voting resolution is proposed after a great deal of discussion among the members. This is something I learnt while going through the minutes of each meeting. Thus, it is likely that the members arrive at a consensus opinion through discussion. (The proceedings of the MPC, by legislation, are kept confidential).

Another explanation is that there’s something similar to an accountability sink at work. Monetary policy is not easy. There are many variables at work, and it is impossible to expect that the intimate knowledge of the economy required to take monetary policy decisions. Note that this is different from technical knowledge.

Money is important and all pervasive in the modern economy. Money forms one half of all exchanges, and changes in the relative price of money (inflation) has economy-wide impact.3 It would be too much to ask of a committee of any size to have all the knowledge required to make the right decisions. In such a situation, unanimity in the decision of the committee helps. Individual members are less likely to be held responsible for the voting decision. This is reflected not only in the final vote but also in the resolution that is to be voted upon.

With monetary policy independence, Tim Harford concludes that with an inflation mandate and an accountability sink, “monetary policy is almost certainly better as a result of the fact that somehow nobody is to blame”. This is when considering the question of increasing interest rates to control inflation.

But what about the failure of the meeting the inflation target? The design of the committee with regard to this may be weak.

There’s another point of weakness in the policy. As per clause 45ZN of the RBI Act, if the RBI fails to meet the inflation target, it must write a report to the Union government explaining the reason for failure, the proposed remedial actions, and the estimated time-period for bringing the inflation rate within the target. In 2022, when the RBI failed to meet its target, the Governor, Shaktikanta Das wrote a letter to the Union Government, but the letter was never made public.

Compare this with the system in the US, where the Humphrey-Hawkins Act of 1978 mandates the Federal Reserve’s chair to semiannually address the Congress, which is live-streamed. For something that affects our everyday life, this is the level of transparency we must demand4.

RBI Monetary Policy as Constrained Discretion

Flexible Inflation Targeting with the given structure of the MPC in India, is an example of constrained discretion. While the MPC is given a target, it does not perfectly have to adhere to it. The costs to the MPC, or the RBI, on failure of meeting the target are relatively low.

As Bottke, Salter & Smith argue in their book, Money and the Rule of Law,

“Constrained discretion is just discretion. No matter how smart or well-intentioned, discretionary central banking is plagued with information and incentive problems. These problems make it systematically unlikely that central bankers can deliver macroeconomic stability.”

We need rules, not discretion. And we need more accountability. It is not sufficient to demonstrate that the performance of the current monetary policy is better than previous ones. The MPC needs to perform better on its own objective.

Notes

Data used in this post: CPI Inflation (Oct 2016 - May 2024) and MPC Votes Data (Oct 2016 - June 2024). The minutes of all the MPC meetings in the period can be found here.

For extracting data from the Minutes and analyzing it, I constructed a ChatGPT Bot, RBI MPC Analyzer. You can also use it if you have a ChatGPT Plus subscription.

When I plot the inflation rates alongside the number of “yes” votes cast in the MPC meeting, most non-unanimous votes correspond to inflation rates below 4%!

For a brief history of development of India’s monetary policy, read this 2020 speech by Shaktikanta Das, the RBI Governor.

This is perhaps not a significant note. But the votes against the RBI Governor among the staffers were cast by only 2 people — Dr. Michael Debabrata Patra and Dr. Viral V. Acharya. Of the 7 RBI staffers who have served on the committee, these are the only 2 I knew very well before looking at the data. I also look up to them academically.

While this seems like an obvious point, I first emphatically learnt this lesson when I read Money and the Rule of Law (2021) by Peter J. Boettke, Alexander W. Salter and Daniel J. Smith.

On Indian regulatory history, the question of independence of regulators, and how regulatory system began in the US, listen to this superb episode of The Seen and the Unseen with Bhargavi Zaveri-Shah.

What an Excellent Read

Great read. Whilst one might argue for the current amount of discretion in monetary policy for the dynamic and evolving market forces, I think that the problem of accountability in case of a failure of rules shall also be a futile attempt. Whom do you point towards in case of a policy failure? A committee with higher constraints? If we approach the policy of more rules, we're left with a major question. These rules need to evolve. What is a mechanism and time frame for updation and who is to be held accountable for failures then. Is a committee that meets often to take decisions based on certain rules not better for accountability in evolving market structures? At least one might be able to point at them as a collective? I do agree with the need for a more lucid and transparent report and maybe revisiting the structure of the same though.